The peaceable impulse of the Welsh in a global context of colonial brutality stands out as a beacon of generosity, yet even this ‘friendship’ served to reinforce, not undermine, the colonising project in Argentina and beyond, writes Lucy Taylor (Aberystwyth University).

In July 2015, people in Argentina’s Chubut Province – and in Wales – commemorated the 150th anniversary of the Welsh colony – Y Wladfa Gymreig. The central theme of the performances and speeches, blog posts, and newspaper articles was the much-celebrated ‘friendship’ between the Welsh settlers and the indigenous communities whom they met. But can colonists and indigenous people really be ‘friends’? Who does that ‘friendship’ serve? And how does it shape power relationships today?

A mixed indigenous-Welsh couple in nineteenth-century Patagonia (Museo Regional Trevelin)

Now a popular tourist attraction, the Welsh community in Patagonia began life in 1865 with the arrival of 153 Welsh-speaking families. They sought to create a new Welsh homeland forged through the Welsh language, reflecting Welsh values, and in defiance of a disparaging ‘English’ elite. The strategy chosen for this anti-colonial enterprise was, paradoxically, the creation of a settler colony.

The myth of friendship is anchored in the story of first encounter, when Cacique Francisco and his wife arrived on a trading mission. The most detailed and reliable account tells us that after initial fearfulness they shared food. However, one of the colony’s leaders suggested that: “’they are just robbers and spies… Kill them both!’”. Everyone else thought differently, though: “‘I will not do that’ said one…’. ‘Let us show more courage and more of our Christian nature than rushing to take the life of an old man and his wife’ [said another]. Everyone agreed with this… In this way we laid the foundations of friendship”.

According to this account, the Welsh resisted the ‘usual’ barbarities of colonial violence and followed the righteous path of Christian charity, adopting a policy of friendship. Of course, the peaceable impulse of the Welsh in a global – and Argentine – context of colonial brutality stands out as a beacon of generosity. However, this ‘friendship’ served to reinforce, not undermine, the colonising project in Argentina – and beyond.

Friendship in Welsh Patagonia was ambiguous, reflecting racialised disdain but also genuine affinity. For example, the indigenous are portrayed in the archive as ‘children of the desert’ and Welsh ‘natural’ superiority as civilised Europeans is never in doubt. They adopted a rule-of-thumb policy that reflected these prevailing geo-racial hierarchies: “let us treat the Indians as we treat each other and even extend to them, as we do to children, the leniency due to ignorance”.

Yet, they also express admiration and gratitude to the indigenous – especially Cacique Francisco (pictured below) – who taught them how to manage the ‘wild’ horses and cows, hunt guanacos, cook and camp, and negotiate the landscape. Outside the Welsh ‘colonial’ milieu, the power relations of friendship shifted – trails, campfires, food and news was shared, and the indigenous became ‘brothers of the desert’ in a tough landscape in which they, and not the Welsh, were at home.

These lived experiences of coexistence and dependence – as well as trade – created a meaningful foundation for genuine friendships, and the acknowledgement that the indigenous people were “the rightful owners of this land”. But at the same time, the Welsh never questioned their own right to settle.

They dealt with the resulting dissonance by adopting a strategy set out in the Handbook of the Welsh Colony which states that: “we cannot disregard the rights of the Welsh-speaking settlements in Chubut Indians of the land… [but] … we should attempt to make friends of them, giving them whatever is honest, whatever is just”. Fair-dealing and non-violence are thus deployed as a powerful tool that can justify settler colonialism.

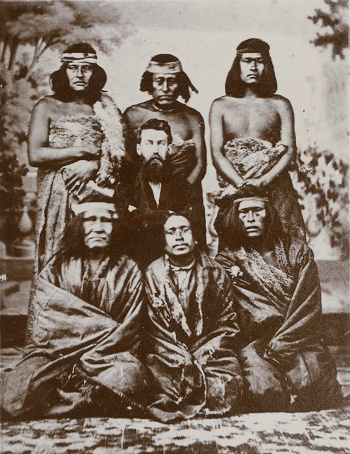

Lewis Jones, a founder of Trelew, with Wisel, Francisco, Yeluk, Waisho, Kichkokum, and Kelchamn in 1867 (Bangor University Archives)

Far from being benign, then, ‘friendship’ can legitimise colonisation by stripping it of the obvious violence associated with political domination, asset appropriation, and cultural oppression. Clothed in the warm and fuzzy sensations of camaraderie and mutual help, shared camp fires and fair trade, colonialism becomes veiled in kindness. Not only does this make colonial relationships harder to spot, it makes colonisation harder to fight, because the usual parade of injustices is masked by acts of sympathy and generosity.

The 150th anniversary of the landing was thus celebrated in Wales as a triumph of Welsh endurance and moral standing, and in Argentina as a nation-building story that provided welcome relief from the usual guilt about indigenous ‘genocide’. The myth of friendship has the power to gloss over colonial relations as effectively today as ever.

However, the Welsh did not set out to violate or oppress, but to avoid oppression themselves. Although their presence strengthened an Argentine nation-building project that would decimate indigenous Patagonian society, Welsh friendship also emerged to resist.

When Argentina launched its Conquest of the Desert in the 1880s, aiming to establish dominance over indigenous Patagonia, the Welsh wrote to army officials “plead[ing] for your clemency”. During an engagement at Valcheta, John Daniel Evans tried to help “my childhood friend, my brother of the desert” to escape, but to no avail.

This kind of friendship really did mean something, but it was powerless to halt the juggernaut of capitalist modernity, state formation, settler colonisation, and global racial hierarchies that were ordering the world.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This post draws on the research article “Welsh-Indigenous Relationships in Nineteenth Century Patagonia: ‘Friendship’ and the Coloniality of Power” (Journal of Latin American Studies, 2017)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting